So far I’ve created a stylesheet and cleaned the document (see The Business of Editing: The AAE Copyediting Roadmap II), and tagged the manuscript by typecoding or applying styles (see The Business of Editing: The AAE Copyediting Roadmap III), inserted bookmarks for callouts and other things I noticed while tagging the manuscript (see The Business of Editing: The AAE Copyediting Roadmap IV), and created the project- or client-specific Never Spell Word dataset and run the Never Spell Word macro (see The Business of Editing: The AAE Copyediting Roadmap V). Now it’s time to tackle the reference list.

Fixing Reference Callouts

Before I get into the reference list itself, I need to mention another macro that I run often but not on all files — Superscript Me. Nearly all of the manuscripts I work on want numbered reference callouts superscripted and without parentheses or brackets. The projects usually adhere to AMA style. Unfortunately, authors are not always cooperative and authors provide reference callouts in a variety of ways, including inline in parentheses or brackets, superscripted in parentheses or brackets, with spacing between the numbers, and on the wrong side of punctuation. Superscript Me, shown below, fixes many of the problems. (You can make an image in this essay larger by clicking on the image.)

I select the fixes I need and run the macro. Within seconds the macro is done. One note of caution: It is important to remember that macros are dumb — macros do as instructed and do not exercise any judgement. Consequently, even though Superscript Me fixes many problems, it can also create problems. My experience over the decade that I have been using this particular macro has been that the fixing is worth the errors that the macro introduces, even though they require manual correction during editing. The introduced errors are few, whereas the fixes are often hundreds.

Tip: Superscript Me is a powerful, timesaving (and therefore profitmaking) macro, but as noted above, it is dumb and just as it can do good, it can do harm — especially to reference lists. Before using Superscript Me on the manuscript, move the reference list to its own file. Doing so will ensure that Superscript Me makes no changes to the reference list, only to the main text material, saving a lot of undo work.

Wildcarding the Reference List

By this point, the reference list has been generally cleaned and moved to its own file.

Tip & Caution: Wildcard macros can be a gift from heaven or a disaster from hell. I like to do what I can to ensure they are a gift and not a disaster. Consequently, I move the reference list to its own file. I know I have said this before, but wildcarding is another reason for separating the reference list from the manuscript file. Often what I want changed in a reference list, I do not want changed in the primary text; similarly, what I want changed in the primary text, I do not (usually) want changed in the reference list. But like all other macros, wildcards are dumb and cannot tell text from reference list. It can do no harm moving the reference list to its own file and working on it separately from the main text, so be cautious and move it.

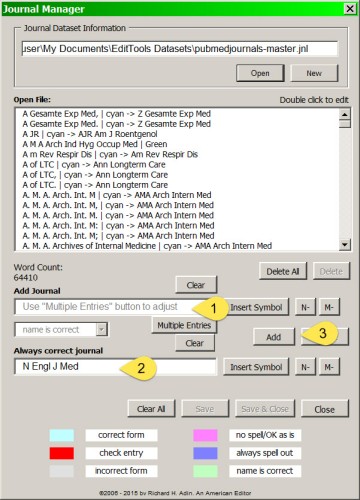

Individual problems, however, have not been addressed. I scan the list to see what the problems are and whether the problems are few or many. For example, if author names are supposed to be

Smith AB, Jones EZ

but are generally punctuated like

Smith A.B., Jones E. Z.

or in some other way not conforming to the correct style, I will use wildcard macros and scripts to correct as many of these “errors” as I can. Wildcards can address all types of reference format errors, not just author-name errors. For example, a common problem that I encounter is for the cite information to be provided in this format:

18: 22-30, 1986.

or

1986 Feb 22; 18: 22-30.

when it needs to be

1986;18:22–30.

These formatting errors are fixable with wildcards and scripts.

Scripts are like a supermacro. A script is a collection of many individual wildcard macros that have been combined into one macro — the script — and run sequentially. One of my reference scripts is shown here:

In the image, the active script file (#1) is identified and what it does (broadly) is described in the description field (#2). The wildcard macros that are included in the script and the order in which they will run are shown in the bottom field (#3). Included is a description of what each of the included wildcard macros will do (#4). For example, the first wildcard macro that the script will run will change Smith, C., to Smith C, and the second wildcard macro to run will change Smith, A.B., to Smith AB,.

The wildcard macros were created using the Wildcard Find and Replace (WFR) macro shown below. In the image, the example wildcard macro (arrow) is the same as the second macro in the script above, that is, it changes Smith, A.B., to Smith AB,.

Creating the macros using WFR is easy as the macro inserts the commands in correct form for you (for more information, see the online description of WFR). Saving the individual wildcard macros, assembling them into scripts, and saving the scripts, as well as running individual wildcard macros or scripts, is easy with WFR. (For some in-depth discussion of wildcards, see these essays: The Business of Editing: Wildcarding for Dollars; The Only Thing We Have to Fear: Wildcard Macros; and The Business of Editing: Wildcard Macros and Money.)

With some projects I get lucky and the authors only have a few references that are a formatting mess and when there are only a messy few, I fix them manually rather than run the macros.

Fixing Page Ranges

If the references are in pretty decent shape (formatwise) so that I do not need to run WFR, I will run the Page Number Format macro (shown below) to put the page range numbering in the correct format For example, the macro will automatically change a range of 622-6 to 622–626, 622–6, or 622.

Making Incorrect Journal Names Correct

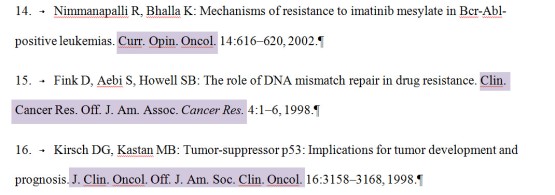

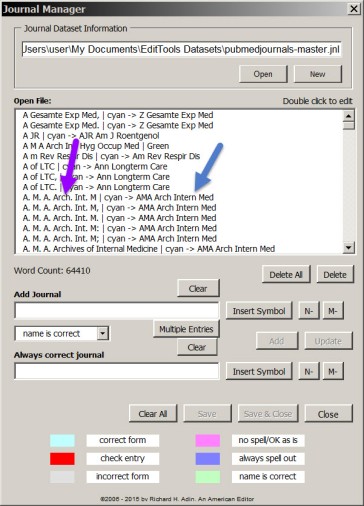

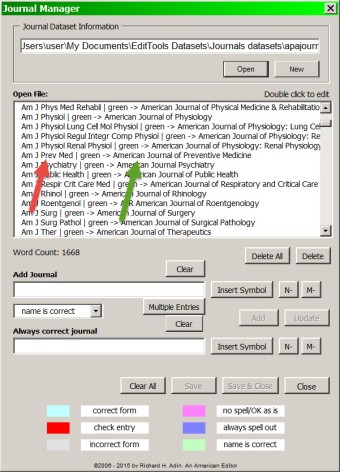

At long last it is time to run the Journals macro. As my journals datasets have grown, they have made reference editing increasingly more efficient. It takes time to build the datasets, but the Journals Manager (shown below) lets me build multiple datasets simultaneously.

As shown in the image, I can build five datasets (arrows) simultaneously. My primary dataset — AMA with Period — has 212,817 journal entries (see circled items).

Tip: Move the reference list to its own file to shorten the time it takes to run the Journals macro. The larger your journals dataset, the more time the Journals macro requires to complete a run. Each iteration of the Journals macro searches from the top of the document to the end as it looks for matches. Leaving the reference list in the manuscript means the macro has that much more to search. In a recent timing test of the Journals macro using my primary dataset and a 50-page document with 110 references without separating out the list, the macro was still running after 2 hours and was not near completion. Running the Journals macro with the same dataset and on the same reference list — but with the list in its own file — took less than 10 minutes. (Think about how long it would take you to manually verify and correct 110 Journal names.)

The Journals macro searches through the reference list for journal names and compares what is in the reference list against what is in the chosen dataset. If the name in the reference list is correct, the macro highlights it in green (#5), as shown below; if it is incorrect, the macro corrects it and highlights the change in cyan (#6). All changes are done with Tracking on.

The Journals macro does two things for me: First, if the incorrect variation of the journal name is in the dataset, it corrects the incorrect journal name so that I do not have to look it up and fix it myself (see #6 above). If the incorrect variation is not in the dataset, the macro makes no change. For example, if the author has written New Engand J. Med but that variation is not in the dataset, it will be left, not corrected to N Engl J Med. When I go through the reference list, I will add the variation to the dataset so it is corrected next time. Second, if the journal name is in the dataset, it highlights correct names, which means that I know at a glance that the journal name is correct and I do not have to look it up (see #5 above).

It is true that the names of some of the more frequently cited journals become familiar over time but there are thousands of journals and even with the frequently cited ones with which I am familiar, correcting an incorrect name takes time.

It is important to remember that time is money (profit) and that the less time I need to spend looking up journal names, the more profit I make.

After I run the Journals macro, I open the Journals Manager (see above) and I go through the reference list, doing whatever editing is required and fixing what needs fixing that my macros didn’t fix. Because of the current size of my journals datasets, there aren’t usually many journal names that are not highlighted. When I come to one that is not highlighted either green (indicating it is correct) or cyan (indicating it was incorrect but is now correct), I look up the name and abbreviation in the National Library of Medicine online catalog and other online sources. When I locate the information, I add it and the most common author variations (based on my experience editing references for more than 30 years) to the five datasets via the Journals Manager.

I take the time to add the journal and variations because once the variations have been added, I’ll not have to deal with them again. Spend a little time now, save a lot of time in the future.

In addition to editing the references for format and content, I also keep an eye out for those that need to be removed from the reference list and placed in text — the personal communication–type reference — and for those that need to be divided into multiple references. When I come across one, I “mark” it using a comment. For example, using the Insert Query macro (which is discussed in the later essay The Business of Editing: The AAE Copyediting Roadmap X), I insert the comment shown below for unpublished material:

When I come to the in-text callout during the manuscript editing, I move the reference text to the manuscript, delete the callout and the reference, and renumber using the Reference # Order Check macro (which is discussed in the later essay The Business of Editing: The AAE Copyediting Roadmap VIII).

Now that the Journals macro has been run and the references edited, the next stop on my road is the search for duplicate references, which is the subject of The Business of Editing: The AAE Copyediting Roadmap VII.

Richard Adin, An American Editor

EditTools: Duplicate References — A Preview

Tags: Bookmarks, Comment Editor, EditTools, Find Duplicate References macro, Journals macro

The current version of EditTools is nearly 1 year old. Over the past months, a lot of work has gone into improvements to existing functions and in creating new functions. Shortly, a new version of EditTools will be released (it will be a free upgrade for registered users).

New in the forthcoming version is the Find Duplicate References macro, which is listed as Duplicate Refs on the References menu as shown here:

Duplicate Refs on the References Menu

The preliminaries

The macro works with both unnumbered and numbered reference lists (works better when the numbers are not autonumbers, but it does work with autonumbered lists). It also works with the reference list left in the manuscript with the text paragraphs and when the reference list has been moved temporarily to its own file (it works, like other reference-specific macros in EditTools, better when the references are moved to a separate, references-only file).

Like all macros, the Find Duplicate References macro is “dumb”; that is, it only finds identical references. The following image shows references 19 and 78 as submitted for editing. (For all images in this essay: For a larger, more readable image, right-click on the image and click “Open link in new tab.” This will open a larger version of the image in a new tab that can be kept open as you read the description of the image.)

Original References

As the image shows, although references 19 and 78 are identical references and are likely to appear identical to an editor, they will not appear identical to the Find Duplicate References macro. Items 1 and 2 show a slight difference in the author name (19: “Infant”, 78: “Infantile”). The journal names are different in that in 19 the abbreviated name is used (#3) whereas in 78 the name is spelled out (#4). Finally, as #5 and #6 show, there are a couple of differences in the cite information, namely, the order, the use of a hyphen or en-dash to indicate range, and the final page number.

Because any one of these differences would prevent the macro from pairing these references and marking them as potentially identical, it is important that the references go through a round of editing first. After editing, which for EditTools users should also include running the Journals macro, the references are likely to look like this:

The References After Editing

If you compare the same items (1 and 2, 3 and 4, 5 and 6) in the above image, you will see that they now better match. (Ignore the inserted comments for now; they are discussed below.) One more step is required before the Find Duplicate References macro can be run — you need to accept all of the changes that were made. Remember that in Word, when changes are made with Tracking on, the material marked as deleted is not yet deleted; consequently, when the macro is run, the Tracked items will interfere (as will any comments, which also need to be deleted). The best method is to (1) save the tracked version, (2) accept all the changes, (3) use EditTools’ Comment Editor to delete any comments, and (4) save this clean version to run the Find Duplicate References macro.

After accepting all changes and deleting the comments, the entries for references 19 and 78 look like this:

The References After Changes Accepted

Running the macro

When the Find Duplicate References macro is run, the following message box appears.

Find Duplicate References Message Box

To run the macro, the macro has to be told where to begin and end its search. If the references are in a separate file from the rest of the manuscript, check the box indicating that the references are in a standalone document (#5) and click Run (#6). If the references are in a file with other material, use bookmarks to mark the beginning and ending of the list as instructed at the top of the message box (#1). To make it easier, the Bookmarks macro now has buttons to insert these bookmarks:

The dupBegin and dupEnd Bookmark Insert Buttons

The Find Duplicate References macro matches a set number of characters, including spaces. The default is 120 (#4) but you can change the number to 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96, or 108 using the dropdown arrow shown at #4 in the Find Duplicate References message box above.

The macro does a two-pass search, one from the beginning of the reference and another from the end of the reference, which is why a list of duplicates may have repetitions.

The results of the search appear like this:

List of Possible Duplicate References

(They appear as tracked changes only if the macro is run with Tracking on; if Tracking is off, the results appear as normal text.) Note the title of the duplicates is “Duplicate Entries (Nondefinitive).” The reason for “Nondefinitive” is to remind you that the macro is “dumb” and there is no guarantee that the list includes all duplicates or that all listed items are duplicated. Much of the macro’s accuracy depends on the consistency of editing, including formatting.

For the examples in this essay, the Find Duplicate References macro was run on a list of 735 references and the list of possibilities shown represents those likely duplicate references the macro found. Note that references 19 and 78 were found (#19 and #78 indicate the portions of those references found duplicated by each pass of the macro); however, if, for example, in editing the page range separator in #19 was left as an en-dash in reference 19 and in reference 78 as a hyphen, the macro would not have listed the material at #19 as there would not have been a match. Similarly, if the author name in reference 19 had been left as “Infant” and in reference 78 as “Infantile”, the macro would not have listed the material at #78 as there would not have been a match.

The next step is for the editor to determine which of the listed possibilities are duplicates. This is done using Word’s Find Navigation pane, as shown here:

Verifying Duplicate References

Copy part or all of what was found (#1) into the Find field (#2). Find will display the search results (“3 matches”) (#3); clicking the Browse button (the rightmost button at #3) lists the three matches found (#4 to #6). The first entry (#4) is always the text in the duplicates list (#1), which means that, in this example, the possible duplicates are #5 and #6. Clicking on the text marked #5 to see the complete text of that entry. Then compare that text to the text of the reference at #6. (It is possible for the macro to find more than two possible matches for the same text — and all, some, or none may be duplicates.)

The Inserted Comment

When editing of the manuscript is finished, have the Reference Number Order Check macro export a renumbering report to send with the edited file to the client. A partial sample report is shown here:

Sample Partial Renumbering Report

Every report bears the creator’s identification information (#1) and file title (#2). You set the creator information once and it remains the same for every report until you change it using a manager. The file title is set each time you create a report.

As the report shows, reference 78 was deleted and all callouts numbered 78 were renumbered as 19 (#3). The prewritten, standard message (a new feature) can be inserted with a mouse click; only the numbers need to be inserted or modified. The report shows that the renumbering stopped at callout 176 (#4) and started again at 197 (#5). Number 6 shows another deletion and renumbering.

Clients like these reports because it makes it easy for authors, proofreaders, and others involved in the production process to track what was done.

The Find Duplicate References macro is a handy addition to EditTools. While it is easy in very short reference lists to check for duplicate references, as the number of references grows, checking for duplicates becomes increasingly difficult and time-consuming. The Find Duplicate References macro saves a lot of time, thereby increasing an editor’s profits.

Richard Adin, An American Editor

Share this: